a few notes

on work and hell

I’m so tired I’m struggling to think. To feel, or rather, to make sense of the feelings. Lost in the overwhelm. I keep having variations of the same conversation with people, you know the one, about capacity, about burn-out, about the sprinting marathon, the inevitable collapse, the what-can-we-do-head-shake, the resigned tone, the kind one, the determined and enraged one; I say the right things. I acknowledge my tininess, my one-person-ness (although I’m not sure about that, honestly, I think we’re never just ourselves), the fact that I have a toddler, a wife, an extended family, all of us with needs right here that require my attention and energy, not to mention my two jobs, etc., but though I say the right things, I do not heed them, these material realities, and instead I feel the crushing forces of grief and anxiety and love mauled by a relentless assault on my spirit, which is divine, yaani tied to God, and it is destroying me in slow and fast ways, in the short and long term.

As it should. If you do not feel yourself being destroyed by what’s occurring in this world, then you are numb—at best—to what makes us human.

I don’t have time to give you a proper update, nor to write the many things I feel compelled to write. I did write this little essay over on Heterosexual Nonsense, about the fascist manipulation of social justice frameworks like “cultural safety” as a mechanism of control for the privileged, which I encourage you to read. It’s a small miracle I managed that much, to be honest, but money is a good motivator, and I’m stuck in hustle mode at the moment. I also wrote this poem, in my ongoing “in the genocide” series that I have been posting directly to social media.

Someone asked on Twitter the other day how anyone is managing to be creative, and I understand entirely the feeling behind that question, the despair. I replied that “the absolute urgency to speak, coupled with the futile repetition of sentences that are not heeded by this militantly racist colonial society, is what keeps driving me back to write more poems. It is equally futile, but at least I take a different direction to arrive there.” There’s truth in that, but also, a degree of false rationalising that I’m familiar with, meaning that I often have to come up with a way of explaining why or how I’m writing when the most answer is that I don’t know. I think of it more like—to borrow an image seared indelibly into my heart by John Murillo—a sparrow with its foot trapped in a car door, beating its “whole bird body madly against it. Trying, it appeared, to bang himself free.” This is the sum of my activities as a writer, a frenzy toward freedom, an incoherence and a song, a small and breakable body once able to soar but caught now in a fixed position, a painful vise.

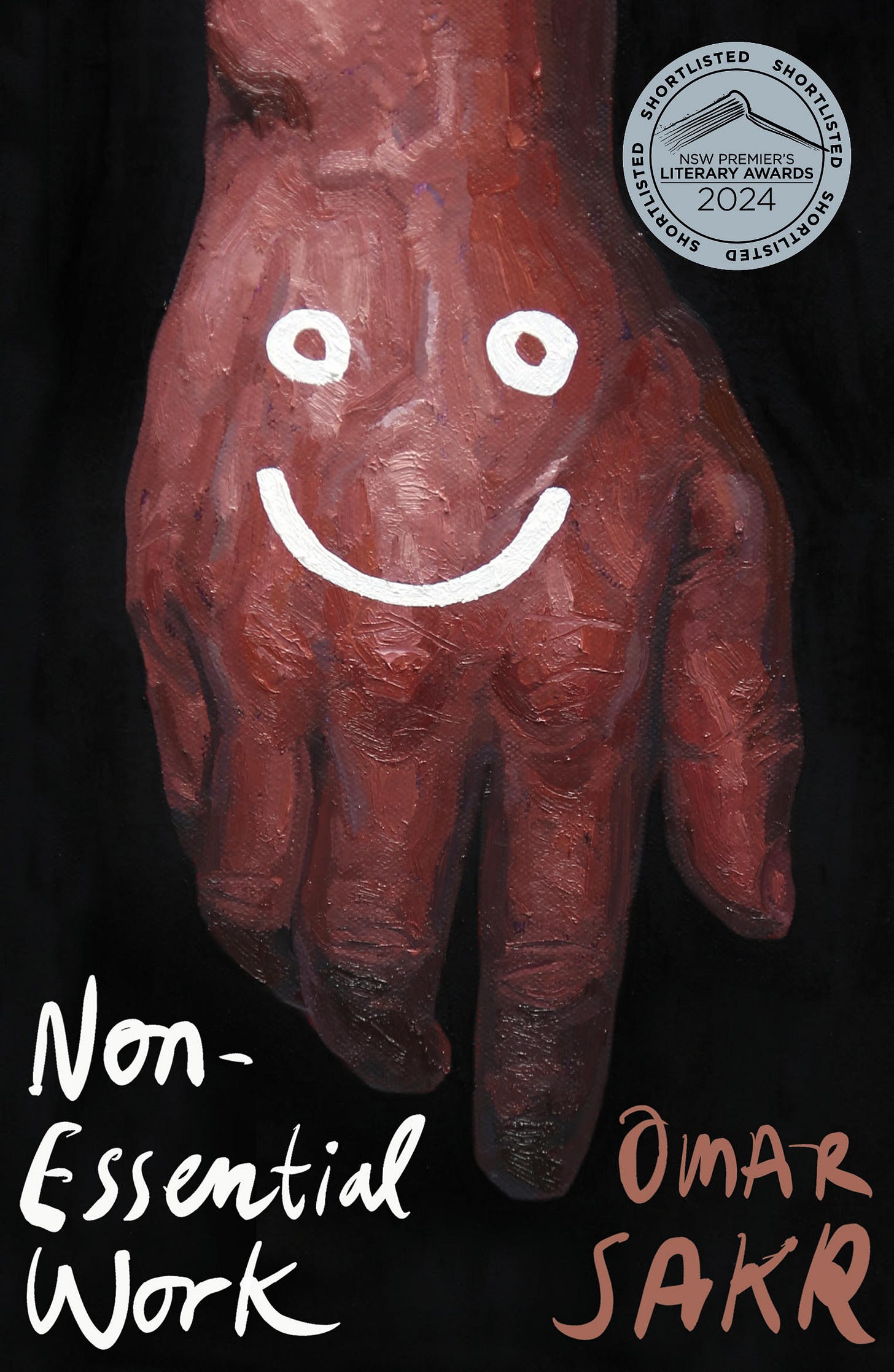

Some work things: my poetry collection, Non-Essential Work, was shortlisted for the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards in the Poetry, and Multicultural categories.

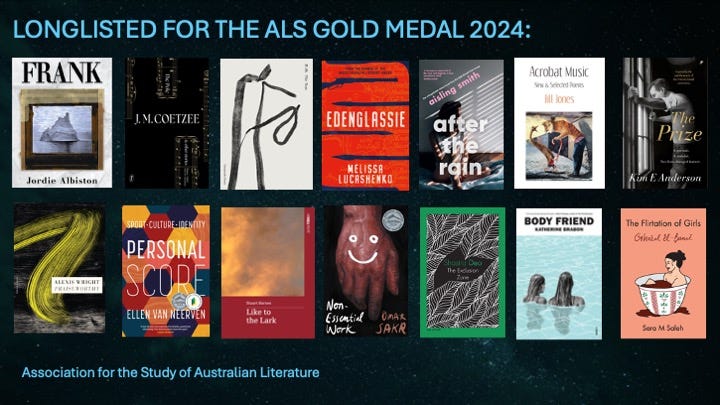

It has also been longlisted for the ALS Gold Medal in an absolutely stacked line-up that includes a Nobel Laureate for Literature in J.M.Coetzee and a future Nobel Laureate for Literature in Alexis Wright, among other luminaries like Melissa Lucashenko.

Next week is the 2024 Sydney Writers Festival, and you can find me reading poetry at A Line in the Sand: Twenty Years of Red Room Poetry on Friday, May 24th at 5pm and at Speak the Light on Saturday at 6pm. Next month, you can catch me at Vivid Sydney, performing for Queeries amidst a towering host of fabulousness 6:30pm-8pm.

On Monday I took my son, who is almost two, to the hospital. He’s been on the public waiting list for six months, and a spot came up. This was his second procedure in three months, and third time in the hospital since October. It was my fifth time, in total, counting when I fractured my spine, and when my wife was hospitalised for a week with liver failure caused by severe viral illness. Each time I have entered the hospital, I have done so in a daze, a glut of horror and awe: look at these lights, this effortless power, the lack of blood and shattered glass, the lack of snipers taking shots at doctors, the lack of bombs raining down. I am so used to seeing footage of Israeli horrors, their genocidal, utterly psychotic assault on every hospital in Gaza with the continued support of the Australian government, among others. How can I be here, I wonder, when they are so happy to be killing us overt there? Us, meaning Arabs, for whom it seems any atrocity is excusable, any depravity acceptable, from the millions killed in Iraq since the 90s through to the invasion of Lebanon, the constant attacks on Palestinians, the depraved US-Saudi mass murder of Yemenis, the proxy wars in Syria.

It feels so unreal, so grotesque. For those of you without children, or who have been lucky enough not to need to go to the hospital with them for surgery, let me tell you something: you are told your child needs to fast beforehand. They will try to schedule you for the morning, early, but there will still be hours where your child is hungry and you cannot feed them. This was our schedule: No solids or formula after 2am. Breastmilk until 4am. Water and clear juice until 6:30am. His procedure ended up taking place around 9:30-10am. In the children’s hospital, in the waiting room, there are bubs and young kids, crying and anxious and miserable and hungry, and there is nothing you can do about it, and for the hours where your kid is hungry and upset because, in my case, he can’t yet ask for food clearly or understand everything we say, you feel like your spirit is being flayed from your body. It is fucking agony. It is hell.

I’m not proud of this next fact, but it is nonetheless true: I am used to Arabs and Muslims being bombed, I am not inured to it, but I am familiar enough with the idea and the images, like an injury I’ve had from birth, a chronic pain, such that I can walk and talk and live my life consciously and unconsciously having adapted to this malaise and only be incapacitated by it sometimes. I am not used to Arabs being starved to death, and having to listen to month after month of commentators and politicians either blithely excuse this or justify it. I’ve said this before, but when the mass starvation of Gaza was announced as a policy in early October, it was a drastic shift, and it is something I bring up in every post because I cannot move on from it. I have stayed here, screaming, because I know what it is like to be hungry—and not just because of Ramadan, with its clearly delineated markers of permissible eating, but one without an end in sight, because we were poor, or because my mother decided I could go a day and a night without and I had to hope she would eventually remember to unlock my door and let me eat.

Even then, I would say I only know what it’s like to be hungry, really hungry, and not to starve. To have your body shut down entirely due to lack. I have seen the bodies of children who starved to death and it is eating away at my heart and mind and spirit, ya Allah. I was in the hospital with its peace and its power, its running water, its lack of violence, its abundance of medicine and painkillers, the calming love of parents and how for the children it was still utterly traumatic, and painful, and horrible. I was thinking of all the children in Gaza who have to survive not just atrocious injuries but surgery without anaesthesia, surgery in the rubble, on the dining room table, I was thinking of the shrieks my son can conjure when he falls or hits his head by accident, because he has no filter, no callous of memories to process pain, so in most cases of even minor bruising it is always the most painful thing he has ever experienced.

I will not catalogue the horrors I have seen to put the above in perspective for you: I don’t need to, I know you have seen at least some of them too. What I will say is that even an unmarked child in Gaza is experiencing an agony nobody should ever experience, and I can’t move on from this. Equally, the frequent images of Israeli settlers, families and children, stopping aid trucks, burning food, spilling it on the floor, are amongst the most awful and depraved scenes I have had the misfortune to witness.

I will never move on from this, nor can I forgive anyone who has.

Salaam,

Omar